Are Amazon ($AMZN), Google ($GOOGL), and Priceline ($PCLN) catering to non-individual investors?

My personal preference is that companies keep their stock price below $200 per share. My logic is simple: it makes it easier to evenly distribute your investment portfolio.

My balanced portfolio logic is quite simple. If you want to balance your portfolio quarterly between 10 great stocks, it is easier with lower-priced stocks. With a stock that is trading at $200, you can easily hold the correct number of shares to be within $100 (half the per share price) of the target value. With a stock that is trading at $1200 per share, the variance is now $600 which can easily throw off the balanced exposure for a small investor like most of my readers.

I discuss two types of portfolios on this site and in my book, The Confident Investor, which you can buy wherever books are sold. The more cautious portfolio suggests a target portfolio allocation for each purchase but is based on a fast-response momentum philosophy that moves that allocation to whichever stock is increasing in price at the moment. The stocks to invest in are chosen by the quality of the company and I list them on my Watch List. This portfolio regularly beats the market over time by at least 20% (if not 50%) regardless if the market is bull, bear, or flat.

The second type of portfolio is much more aggressive and often is 3X-4X the market increase in a bull market. However, it is not as safe in a flat or bear market. This strategy evenly divides a portfolio among 15 great companies that are growing their stock price faster than the others on my Watch List. I recalculate the top 15 and rebalance the portfolio quarterly.

In both portfolios, it is easier to balance the portfolio or allocate each portion of the portfolio if the stock price is under $200. When the stock is over $200, most investors that are working with a portfolio under $250,000 find themselves to heavy or too light in high-cost stocks.

You can see the performance of my version of both portfolios by reading my regular posts that are in the category Weekly Portfolio Gain. You do not need to have read my book to see these results although you may not understand how I create the list of companies.

Stock splits, once considered a way to keep shares affordable for mom-and-pop investors, are rare today as companies aspire to new heights.

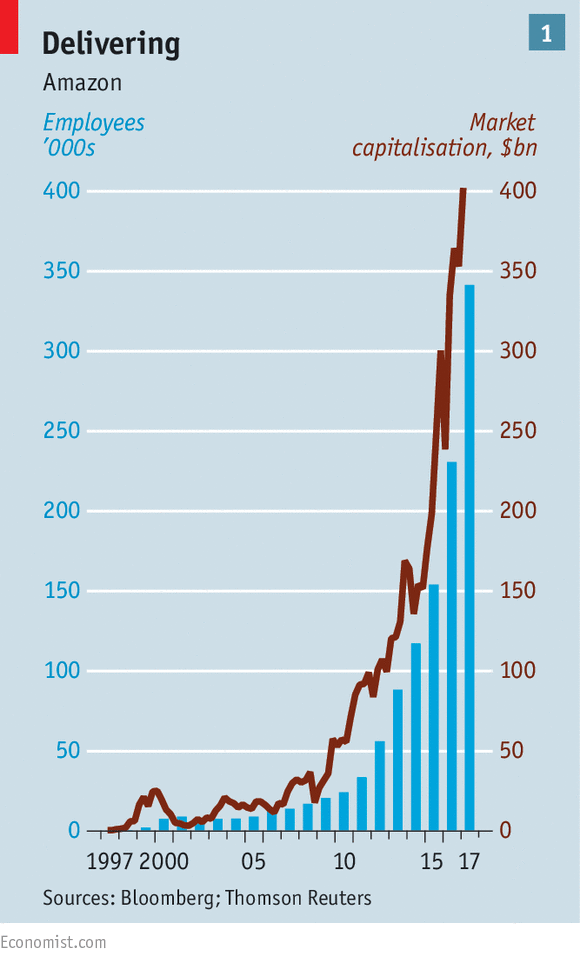

Amazon [stckqut]AMZN[/stckqut], Google [stckqut]GOOGL[/stckqut], and Priceline [stckqut]PCLN[/stckqut] are recent examples of companies that have let their stock prices approach or exceed a four-figure price.

In the 1990s, when stock picking for one’s own account was in vogue, companies also considered splits a way to keep shares affordable for mom-and-pop investors. Even though nothing changes fundamentally about the company with a stock split—it’s like trading a dime for two nickels—splits used to generate excitement and, often, a short-term pop for the shares.

In recent years, though, individuals have gravitated toward index funds. And institutional investors don’t like stock splits, because increasing the number of shares increases their trading costs.

The godfather of the no-split camp is Berkshire Hathaway Inc. [stckqut]BRK.A[/stckqut] Chairman Warren Buffett. Berkshire’s Class A shares are the priciest U.S.-listed equities at the time of this writing. For years, Mr. Buffett said he didn’t want to split the shares because he didn’t want to attract people who found such a move to be a good reason for buying a stock. “People who buy for non-value reasons are likely to sell for non-value reasons,” he said in a 1984 letter to shareholders.

There are reasons behind the trend. Before the rise of discount brokerages and a decline in trading commissions in the 1990s, even small-time investors often had to buy shares in round lots of 100, which meant that a high price could make such a purchase prohibitively expensive. These days, though, retail investors can buy as little as one share, and often pay commissions of $10 or less.

Academics who have studied share splits have also posited that executives who split their company’s stock may be motivated by a desire to keep their share prices from looking expensive. Now, some companies and their investors seem to treat higher stock prices as a sign of accomplishment. Of course, this bragado is just as foolish as calling a $50 stock: cheap.

A fair concern is companies may have held off on splitting shares in recent years in response to the financial crisis, when stock prices dropped sharply and some big companies were humbled into performing reverse splits to raise their share price to avoid being delisted. Reverse stock splits are embarrassing and painful and of course being delisted is the equivalent of death in the stock market.

Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos hasn’t ruled out the idea of a split, which the firm did three times as a young public company. A shareholder at Amazon’s annual meeting in Seattle on Tuesday asked Mr. Bezos if he would consider splitting the company’s shares to give members of the middle class and younger people the chance to afford the shares.

You can purchase my book wherever books are sold such as Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and Books A Million. It is available in e-book formats for Nook, Kindle, and iPad.

Source: Amazon’s Brush With $1,000 Signals the Death of the Stock Split

Commenting on Amazon.com, Inc.’s [stckqut]AMZN[/stckqut] first quarter results, MKM Partners said the pace of investment spending by the online retail behemoth isn’t moderating and investors are supportive.

Commenting on Amazon.com, Inc.’s [stckqut]AMZN[/stckqut] first quarter results, MKM Partners said the pace of investment spending by the online retail behemoth isn’t moderating and investors are supportive.